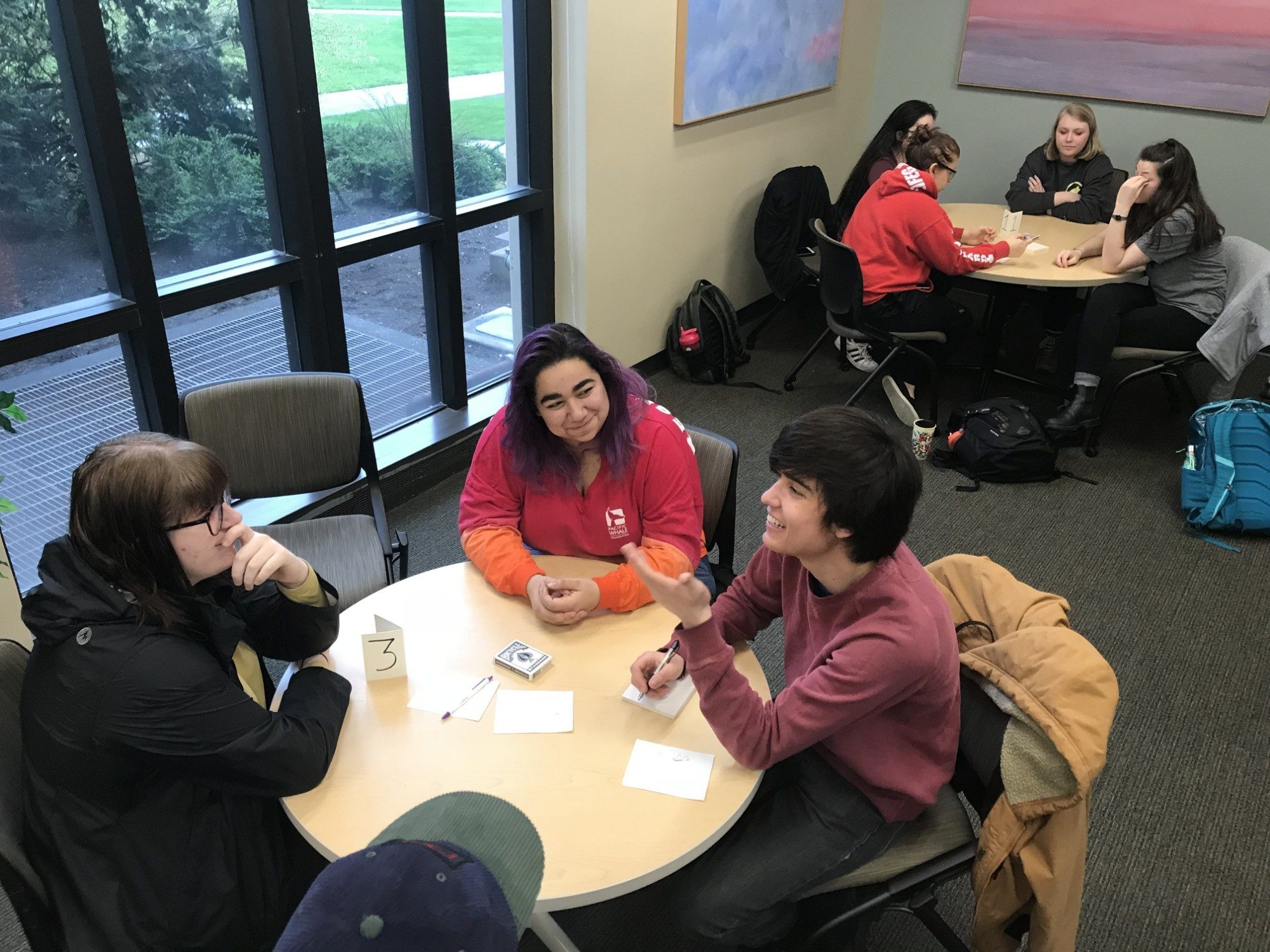

The power of peer educators to help your students practice We worked hard to become experts in our fields. We faculty work hard to plan and teach our classes. And now a pandemic has us working hard to continue and refine the shift to remote teaching. As professionals in teaching within higher education during trying…Continue Reading Practicing What You Teach

Practicing What You Teach