What if white professors like me spent less time denying our racism and more effort exploring its factuality?

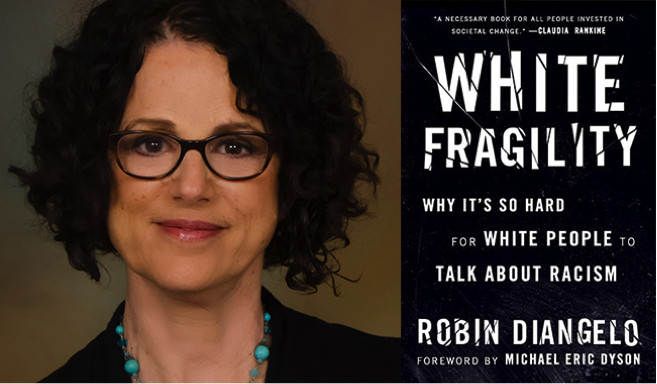

One of the most vital books I have read in years builds a case for taking on this provocative challenge. White Fragility: Why it’s so Hard for White People to Talk about Racism (2018) by Robin DiAngelo draws upon a rich legacy of sociology to offer a lifetime of lessons few have had the chance to think through.

Carrying forward the subject of 2018’s Faculty Development Day on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the University, the College of Arts & Sciences chose White Fragility as this year’s title for its annual faculty reading group. Copies were given to CAS faculty, for participation in a discussion last Thursday, led by Drs. Lauren Alfrey and Lara Trout. (Past years’ selections in this series have included Make it Stick: the Science of Successful Learning, Academically Adrift, The Slow Professor, Learner-Centered Teaching, and My Freshman Year: What a Professor Learned by Becoming a Student.)

While the book is not specifically about teaching, the fact that 90% of UP’s instructors are white – and the fact that so few of us are comfortable talking about race – make it deeply relevant to our campus. The department I chair (English) is entirely white. When students scroll through our Faculty Profiles page, what message does this racial homogeneity broadcast about our major, our discipline, and our university?

While over a third of our undergraduates are nonwhite, only a tenth of current UP faculty are (45 out of 445). This is even less diverse than the national average (84% of America’s college professors are white; for school teachers, the figure is 82%). The book’s lessons could have a significant impact on our university’s hiring practices, admission rates, classroom atmosphere, and the future citizens we graduate.

While it’s true that race is a scientific fiction, it is also a social reality. And while race is only one dimension of our complex identities, it is the one white Americans are least educated about. DiAngelo — who grew up white, urban, and poor in America – aims to raise the racial consciousness of white people, a group that usually feels exempt from the entire subject of race, and has historically refused to learn about its history and legacies of inequality.

And so the first goal she urges us toward is to see the racism around us. While most of us think of racism in terms of individual acts, DiAngelo insists that “racism is a structure, not an event” (28). She defines racism not as “conscious intolerance” but as the ambient system of inequality we live in, have inherited, and, for white people, profit from.

What holds this system in place, even in the post-civil-rights 21st century, are such things as implicit bias, white solidarity, de facto segregation, and living in a culture of implicit racial supremacy. As DiAngelo explains, white peoples’ blindness to racism also comes from a series of ideologies, such as those of individualism, meritocracy, and color blindness. These incomplete frameworks shield most white people from seeing our participation and complicity in a system of racism. And when confronted with contrary evidence, our reaction is predictably defensive and hostile (“we rely on such flimsy evidence to certify ourselves as racism-free” [80]). As an alternative to reactions of denial, DiAngelo suggests we “focus on how – rather than if – our racism is manifest. … stopping our racist patterns must be more important than working to convince others that we don’t have them” (129).

Insulated from the kind of race-based stress people of color are subject to daily, white peoples’ understanding of race goes unchallenged. The few times we are challenged, we react with predictable drama, which DiAngelo diagnoses as “white fragility,” a term she defines as “the sociology of dominance: an outcome of white people’s socialization into white supremacy and a means to protect, maintain, and reproduce white supremacy” (113). This fragility is a strategy for maintaining a racist status quo – for not engaging in further dialogue, and understanding.

Toward a solution, she calls for something academics should already be good at: education. Collectively, American whites need to become better informed about race and how racism works – to pay more attention to a subject we thought we were supposed to ignore: “consider racism a matter of life and death (as it is for people of color), and do your homework” (145).

This does not involve a moment of becoming “woke” but a lifelong process: “we must never consider ourselves finished with our learning” (153). Her book offers ways to take responsibility for structural racism by becoming more aware of our behavior, more reflective and open (rather than defensive), and more willing to change our behavior (113): “Interrupting racism takes courage and intentionality” (153).

UP can become a force of change within a culture of racism, but as DiAngelo shows, it will take significant works of honesty, openness, humility, and historical vision on the part of white people – or else we will continue to be complicit in a culture of silent racism.

If you are interested in a free copy of White Fragility, CAS still has a dozen left: until the copies are gone, you can get one from Zach Muñoz’s office in the Dean’s Suite Buckley Center 201.

Really nicely explained, thanks! –mm