A good college education, even in the best of times, requires having difficult conversations. We can only learn and grow when confronted with new ways of thinking; engaging diverse and challenging ideas in an inclusive educational community is central to a liberal arts education and essential to the University of Portland Core curriculum. These particular times (November of annus horribilis 2020), however, are not the best – making the having of difficult conversations more fraught. And, just maybe, more important.

There is, unfortunately, no magic formula – but there are lots of recipes, and a general sense that good teaching requires thoughtful attention to creating classroom (or Zoomroom) communities that make difficult conversations healthy and educational. Michael Roth, the president of leading liberal arts university Wesleyan, writes about making “safe enough spaces” where colleges balance a careful attention to student well-being with the necessity of being exposed to different and uncomfortable viewpoints. In our deeply divided country, we need spaces where we can learn and feel a sense of inclusive community even if we don’t agree.

Some of the recipes I’ve come across are less specific to higher education, but may have relevance at this cultural moment. Organizations such as Braver Angles and Essential Partners (see also here), for example, both have guides specific to political conversations “across the red-blue divide.” James Madison University has also put out a guide for their academic community about “Facilitating Difficult Election Conversations.”

In other domains, in organizing “peer-to-peer conversations about race” last summer UP’s Office of International Education, Diversity, and Inclusion offered a “Guide to Respectful Conversations” by the non-profit Repair the World. I’ve also had psychology colleagues point me to a University of Michigan guide on “Intergroup Dialogue.”

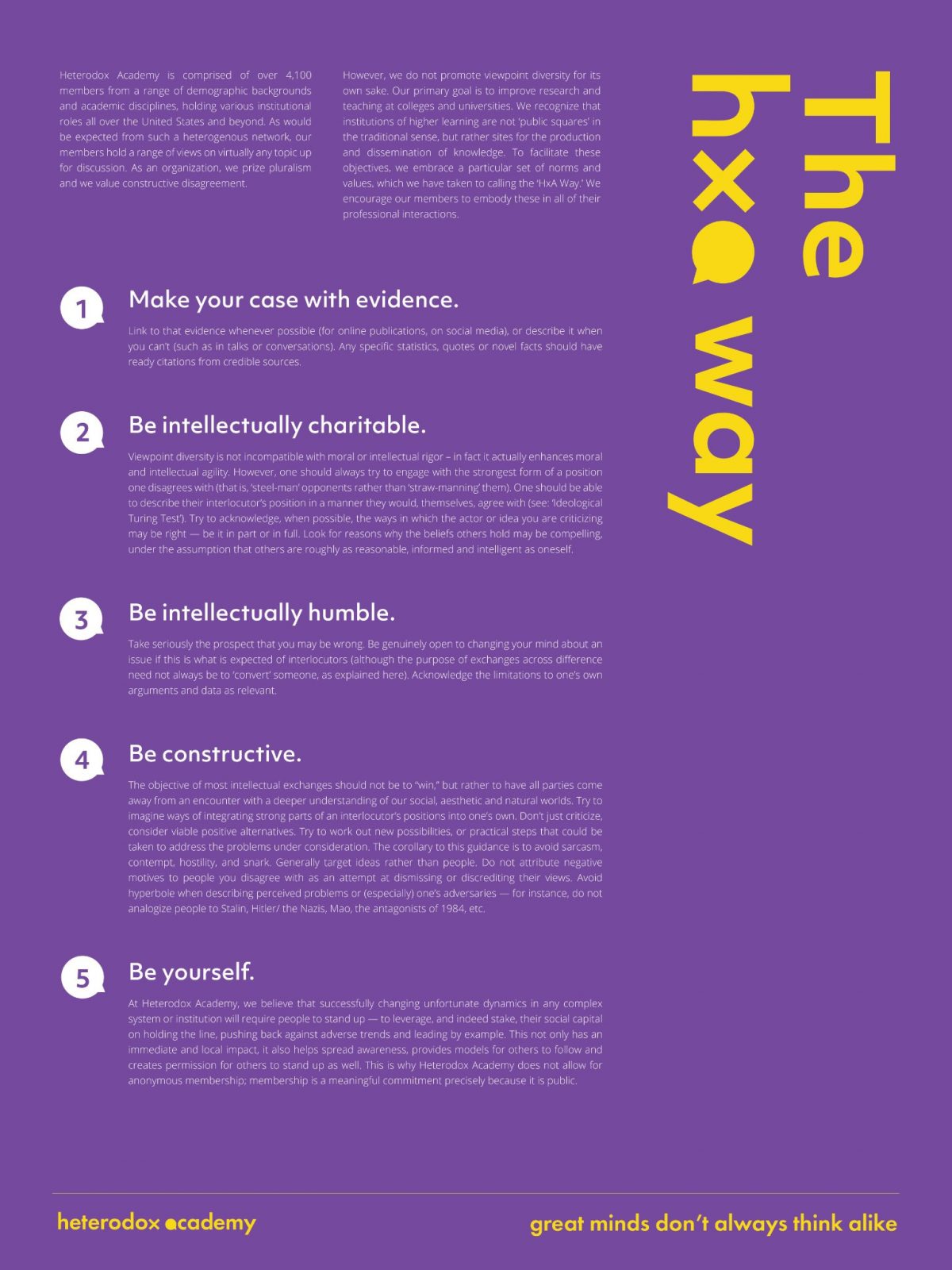

My personal favorite, likely because it was formulated by social scientists thinking specifically about academic contexts, is the guidelines from the Heterodox Academy. The group itself tries to promote ‘viewpoint diversity’ in higher education, and I don’t always agree with all of their approach. But that, I suppose, is part of the point: to disagree, but still learn.

Their guidelines, which I do really like, include five points of emphasis:

Make your case with evidence. In my own classes I find students often default to talking about issues by prefacing “I feel that…” or “I believe that…” and those kinds of framings can be important in some contexts – it is good to have feelings and beliefs. But I tell students that in academic contexts, or at least in social science, as much as possible we want to focus on evidence – what do we know from research, observations, and direct experience?

Be intellectually charitable. This one is relatively simple: for discussion and learning, start by assuming someone you disagree with might be right. Be willing to explore a reasonable other position deeply, for the sake of understanding.

Be intellectually humble. This one is also simple: assume your position might be wrong. Be genuinely open to changing your mind.

Be constructive: This one may be the most important: don’t approach challenging academic discussions with the goal of being right or proving another wrong. Approach academic discussions as a chance to learn. As the Heterodox Academy puts it “target ideas rather than people.”

Be yourself: In our increasingly virtual lives, it can be easy to hind behind blank screens and user (rather than real) names. But we learn more when we are present with our real selves.

I’ve started sharing these ideas with my students, and keeping them in my own mind as I confront challenging conversations of both academic and non-academic types. They are surprisingly hard to execute. Respecting evidence, being charitable, being humble, being constructive, and being present are not the direction our broad cultural discourse seems to be moving. But, at least in classrooms and when trying to bring the values of the liberal arts to our students, they might help us learn from our difficult times.