People sure are funny about money!

We’re weird about money. So why should we expect government to be any different?

A few weeks ago the line outside the Portland State University Ben & Jerry’s stretched from the shop to the PSU Recreation Center and then looped back around a few weeks ago, when the ice cream shop held its annual Free Cone Day, and that was in the rain. Last year, with slightly better weather, people waited an average 45 minutes in order to save four bucks on a cone, according to business manager Jim Cooper.

Explanation? “People like free stuff,” says Cooper.

We’re all irrational when the subject is money, say the psychologists and economists who study these things. We’ll fritter away 45 minutes to save $4 on an ice cream cone but think nothing of spending $4 on lattes five days a week. Anybody wondering why government is so often so wrong about money should just look in the mirror, say the experts.

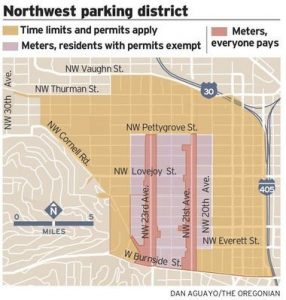

Few topics get Portlanders hotter under their collars than parking. A few weeks ago the Northwest Parking District Stakeholder Advisory Committee held a meeting in a packed room full of angry residents. The unusual turnout was due to a discussion about a proposed increase in the cost of on-street parking permits.

Two years ago the city implemented a parking plan that cost $60 per car, and the city promised the money generated would go toward implementation and enforcement of the plan.

Now the city is about to raise the permit price to either $300 a year, which was endorsed by the neighborhood association, or $180 a year, which was endorsed by the advisory committee. At the same time, the Central Eastside Industrial District is seeing the cost of its street parking permits rise to $300 a year.

“Group think” is what has led to the precipitous increase, says Tavo Cruz, a member of the Northwest Portland neighborhood association as well as a member of the advisory committee. Cruz describes a process in which the committee was established to work on one goal—establishing the permits to keep non-residents from parking on the street all day—and then expanded its vision to larger goals.

Cruz says he voted for the increase to $180, so maybe the group think may have infected him as well. “My fear about this is we could eventually wind up with the worst of all situations, which is an expensive program and no improvement for parking,” he says. “And that’s where it becomes irrational.”

That’s also were it becomes typical of the way committees and organizations tend to operate, says Mark Meckler, a University of Portland economist and business consultant. “Classic institutional theory” is what Meckler calls the process described by Cruz. Committees and bureaucracies usually begin with a narrowly-focused goal, Meckler explains. Then, they turn into institutions.

“Over time the goal of the organization starts to shift from achieving its mission to self-existence,” Meckler says. “It becomes like an organism.”

In this case, the increased parking permit fees in Northwest and inner east side will generate considerably more revenue than the $60 permits residents were told were needed to finance enforcement. So where is all that extra money going? Now the permits are being viewed by the committee as revenue generators, according to Cruz, and the money can be spent on a wider range of transit projects.

Incidentally, Meckler says there’s a reason the parking advisory committee faced a packed house public meeting and Kahn’s audit showing $33 million in waste provoked hardly a whisper. It’s called Parkinson’s Law, authored by C. Northcote Parkinson, who claimed that the time a committee spends on an agenda item will be in inverse proportion to the amount of money involved.

The city’s $33 million financing and HR boondoggle was ignored because it was complicated. “Nobody wants to sound like an idiot on a complex subject or an amount of money out of our ability to comprehend,” Meckler says. “It’s easy to speak up on wasting an amount of money that you can understand.”

It isn’t irrational for humans to want to protect their own jobs, but it might be irrational to assume bureaucrats will do what’s best for the city if that will make their jobs less secure, says Meckler. That’s basic agency theory, according to Meckler, which states that the higher up individuals climbs in an organization the less likely they are to take risks that will jeopardize their jobs.

Government is always at the mercy of agency theory, according to Meckler, which means creative, bold solutions to problems will be avoided in favor of safe, incremental change.

Parking Permits are not the only areas affected by this type of thinking. Portland’s low-income housing initiatives are getting the short end of the bargain as “taxpayer money devoted to building low-income apartments is providing one-third as many apartments as it could.”

Credits – from an article by Peter Korn Portland Tribune.