The routines and habits of celebrated writers provide a subject of perpetual fascination. Readers hunger for the preferably wretched details of artistic creation. If idiosyncrasy is good (John Cheever typing in his underwear, Vladimir Nabokov standing up to shuffle a deck of index cards into Lolita, Truman Capote lying down with coffee and a cigarette), stamina, duress, and deprivation are better (Jean-Paul Marat scratching out revolution atop a box beside the bathtub in which he cooled his scorching psoriasis, the visually impaired James Joyce wearing a white jacket better to illuminate the page, Mavis Gallant pawning her typewriter and starving in Madrid while her agent hoarded her New Yorker checks).

Perhaps what we admire most in writers is their ability to vanquish the noise of life—from the low hum of the quotidian to the high whine of crisis—by achieving a state of deep concentration that seals them, in the most extreme cases from physical or emotional pain, but more often simply from the insistent, contrary rhythms of responsibility. Consider the case of the prolific novelist Anthony Trollope, who arose at 5:30 every morning to write steadily for three hours before breakfasting and heading off to a day’s work as a postal surveyor.

A world that celebrates the hyperattention technology abets tends to regard the sort of deep attention still required for not just the writing life and but all those lives that demand the solving of difficult problems as rather antiquated and unfashionable. Despite the warnings of cognitive scientists about important limitations to our multitasking capacity, and about the overconfidence multitasking breeds, our commitment to it seems only to grow. Perhaps there is no better test of deep attention than the ability to write while the bombs are falling; and the most persuasive exemplar of such determined focus I know is Ulysses S. Grant.

Grant earned his nickname— “Unconditional Surrender” Grant— from his refusal to offer any concessions to the Confederates at Tennessee’s Fort Donelson, which he attacked in 1862. “No terms,” Grant informed his adversary and old acquaintance, Simon Bolivar Buckner, “except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.” Unconditional surrendermight equally well describe Grant’s approach to writing, an enterprise to which he gave himself over with single-minded focus. Horace Porter, a member of the general’s staff, offers a portrait of his commander at work: His powers of concentration … were often shown by the circumstances under which he wrote. Nothing that went on around him, upon the field or in his quarters, could distract his attention or interrupt him. Sometimes, when his tent was filled with officers, talking and laughing at the top of their voices, he would turn to his table and write the most important communications. There would then be an immediate “Hush!” and abundant excuses offered by the company; but he always insisted upon the conversation going on, and after a while his officers came … to learn that noise was apparently The routines and habits of celebrated writers provide a subject of perpetual fascination. Readers hunger for the preferably wretched details of artistic creation. If idiosyncrasy is good (John Cheever typing in his underwear, Vladimir Nabokov standing up to shuffle a deck of index cards into Lolita, Truman Capote lying down with coffee and a cigarette), stamina, duress, and deprivation are better (Jean-Paul Marat scratching out revolution atop a box beside the bathtub in which he cooled his scorching psoriasis, the visually impaired James Joyce wearing a white jacket better to illuminate the page, Mavis Gallant pawning her typewriter and starving in Madrid while her agent hoarded her New Yorker checks). Perhaps what we admire most in writers is their ability to vanquish the noise of life—from the low hum of the quotidian to the high whine of crisis—by achieving a state of deep concentration that seals them, in the most extreme cases from physical or emotional pain, but more often simply from the insistent, contrary rhythms of responsibility. Consider the case of the prolific novelist Anthony Trollope, who arose at 5:30 every morning to write steadily for three hours before breakfasting and heading off to a day’s work as a postal surveyor. A world that celebrates the hyperattention technology abets tends to regard the sort of deep attention still required for not just the writing life and but all those lives that demand the solving of difficult problems as rather antiquated and unfashionable. Despite the warnings of cognitive scientists about important limitations to our multitasking capacity, and about the overconfidence multitasking breeds, our commitment to it seems only to grow. Perhaps there is no better test of deep attention than the ability to write while the bombs are falling; and the most persuasive exemplar of such determined focus I know is Ulysses S. Grant. Grant earned his nickname— “Unconditional Surrender” Grant— from his refusal to offer any concessions to the Confederates at Tennessee’s Fort Donelson, which he attacked in 1862. “No terms,” Grant informed his adversary and old acquaintance, Simon Bolivar Buckner, “except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.” Unconditional surrendermight equally well describe Grant’s approach to writing, an enterprise to which he gave himself over with single-minded focus. Horace Porter, a member of the general’s staff, offers a portrait of his commander at work:

His powers of concentration … were often shown by the circumstances under which he wrote. Nothing that went on around him, upon the field or in his quarters, could distract his attention or interrupt him. Sometimes, when his tent was filled with officers, talking and laughing at the top of their voices, he would turn to his table and write the most important communications. There would then be an immediate “Hush!” and abundant excuses offered by the company; but he always insisted upon the conversation going on, and after a while his officers came … to learn that noise was apparently a stimulus rather than a check to his flow of ideas, and to realize that nothing sort of a general attack along the whole line could divert his thoughts from the subject upon which his mind was concentrated.

On the road Grant never liked to retrace his steps. When lost, he would carry right on rather than turning around. He seemed to have had the same superstition about his prose, which he crafted, as Porter documents, with relentless efficiency:

His work was performed swiftly and uninterruptedly, but without any marked display of nervous energy. His thoughts flowed as freely from his mind as the ink from his pen; he was never at a loss for an expression, and seldom interlined a word or made a material correction. He sat with his head bent low over the table, and when he had occasion to step to another table or desk to get a paper he wanted, he would glide rapidly across the room without straightening him-self, and return to his seat with his body still bent over at about the same angle at which he had been sitting when he left his chair.

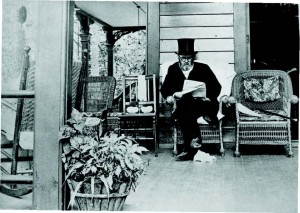

Fastidious about language, Grant was indifferent to tools and surroundings alike. Nothing could distract him. In the field “he wrote with the first pen he happened to pick up,” sharp or blunt, “good or bad” His desk “was always in a delirious state of confusion” —a “literary geography,” Porter tells us, that baffled everyone except Grant, who could find a document he wanted “even in the dark.” The unshakeable concentration that Grant exhibited in the field also enabled him to complete his memoirs as he was dying of throat cancer two decades later, all the while convinced that each word he wrote hammered “another nail” in his coffin. The style of the memoirs, like that of the wartime writings, is distinguished by economy and precision.

Our current discourse about war veers from euphemism—kinetic operations, persistent low-intensity conflict, hearts and minds—to a deeply romanticized, unreflective rhetoric about heroes and values, to the equally and paradoxically romantic language of knowingness, cynicism, and disaffection inherited from pop-culture depictions of Vietnam (“Apocalypse Now speak,” one might call this last category). It is all or nothing; there is no room for ambiguity.

Caught between gauzy nostalgia for a “good war” and the current realities of a dubious one, today’s discussions are too often muddied by a reluctance to acknowledge that the deaths of good people in bankrupt causes do nothing to ameliorate those causes, or that armies serving just ends comprise soldiers with a wild variety of motives. Americans seem constitutionally incapable of accepting that even a “good war” is never fought for a single good cause alone nor ever won without brutal methods.

Grant fought in two wars, the Mexican War and the Civil War. The latter he believed a war of principle, the former “one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.” But he never allowed the fact that brave men died in Mexico to distort his opinion of its politics, nor did he permit his belief in the cause of union to gild the waste of human life that secured it. More than a century has passed since Grant’s death, and we are at war again, or still. His writing reveals another way to talk about war.

To his wife on his first battle:

There is no great sport in having bullets flying about one in evry direction but I find they have much less horror when among them than when in anticipation. menced with such vengence I am in hopes my Dear Julia that we will soon be able to end it.

On his second:

[T]he battle of Resaca de la Palma would have been won, just as it was, if I had not been there.

On his first mission in command during the Civil War:

I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to call a halt and consider what to do; I kept right on.

On the character of Zachary Taylor:

No soldier could face either danger or responsibility more calmly than he. These are qualities more rarely found than genius or physical courage.

On the surrender of Robert E. Lee:

That much talked of surrendering of Lee’s sword and my handing it back, this and much more that has been said about it is the purest romance.

Perhaps Grant’s philosophy of composition is best expressed in his description of the letter he sent to Lee accepting the latter’s surrender: “When I put my pen to the paper I did not know the first word that I should make use of in writing the terms. I only knew what was in my mind, and I wished to express it clearly, so that there could be no mistaking it.” Grant loves that final phrase. He repeats it several times in theMemoirs to describe both his own prose style and that of his hero Taylor.

A friend likes to tease me that there is no conversation into which I cannot smuggle a mention of Grant. When it happens—when my mind works itself around from an apparently unrelated subject to the Civil War general—she’ll say, “Ah, Grant!” as if he’s a mutual acquaintance she hasn’t heard news of in a while: “There he is. It was only a matter of time.” She’s right, of course: Grant is my idée fixe. (How many people can say that?) I’ll drop his name at what may seem the most unlikely moment. It just seems to me the right connection to make in so many circumstances, especially in recent years, when we have taken to talking about war in ways that differ profoundly from the clear-sighted, plain-speaking mode that was second nature to him.

Not infrequently, on a Sunday afternoon, as the church bells sound through Morningside Heights, I make my way uptown for a visit to the General Grant National Memorial, a.k.a. “Grant’s Tomb.” Dedicated in 1897, this massive granite pile was modeled after Mausolus’s at Hali carnassus. Groucho Marx long ago turned the tomb into a joke by asking who was buried there, and the memorial’s neglect has periodically provoked Grant’s relatives to threaten to remove his remains to Ohio. On a recent trip I overheard one tourist say to another: “I didn’t even know we had a president named Grant, did you?” When I visit, I think chiefly of Grant the writer rather than of the president or even the general. He would have found the place far too quiet: no bombs falling, nothing more than the occasional whispered conversation to stimulate his deep attention