Many of the men were so badly wounded they were flown directly from the battlefield in Vietnam to the hospital, and the nurse would clean battlefield dirt from their wounds. The men were Marines. Many of the men had lost hands and feet and legs and arms. The men would ask the nurse to scratch their missing limbs and she would do so, her fingers scrabbling in the hollow air, and they would lean back pleased and grateful.

She was 22 years old. She had just graduated from the University of Portland with her nursing degree, and passed her nursing boards, and gone through Officers School, and earned her rank, and been assigned to the Naval Hospital. She is the beam ing child on the next page. Sometimes all 120 beds in the ward were filled and she would be the only nurse on night duty with a few Navy corpsmen as assistants.

Did they give you grief sometimes, you being the only woman, and so young?

No, she says, smiling but firm. I was their officer. They called me ma’am or they called me Miss Randles.

Did you ever break down and cry and despair at such carnage among such tall children?

There were days I sobbed, sure, she says, not smiling, but that was more fatigue than despair. The shifts were long. There were hard hours but they were proud men and I was proud of them and we were too busy to despair. I wanted to treat them like the strong, handsome Marines they were. You’re not just your arms and legs. You’re not just your injuries, your missing parts. People recover. People heal. People are people, not just parts. I was always fascinated by recovery. I loved working in stroke units and with amputees. I thought about being a surgeon but nursing seemed more fun, more intimate.

Infection was the great enemy, she continues. You get blown up, you’re in dirt, you’re easily infected —that’s the enemy. We watched like hawks for necrotic tissue. We fought temperatures all night long. The men were fitted with prosthetics and we would help them get used to their new parts. I heard a lot of swearing. Mostly I heard banter and byplay and jokes and humor and teasing. A lot of music. Not many visitors—none of the men were in their hometowns there. They got mail and cookies and blankets from home. There would be a celebration when a guy left for home.

They’d all go outside and see him off. Wheelchair guys would all roll outside too. It was pretty much one in and one out every day. A lot of guys came in during the Tet Offensive.

None of my men died, she says. Not one. We cared for maybe two thousand men in two years. I can still see most of their faces. I can still smell vinegar and bleach and infection. Infection has a sickly sweet smell. I got paid $300 a month. Sometimes my car ran out of gas because I was too tired to remember to fill the tank. We never talked politics. They did talk about where they had been, and where they’d been blown up, and about their buddies back in the war. Remember that these were volunteers, not draftees. They were proud of their service. They were proud that they didn’t let their buddies down. Part of them was still in the war: a bedpan fell off a bed with a crash, and they’d all dive for cover. They were heroes to me, she says. Heroes, do you understand? They were so brave, so tough, so cheerful, so enduring. They deserved respect, and I did my very best to deliver them respect.

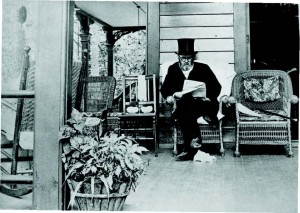

She doesn’t say anything for a while and then she opens her scrapbook and shows me a letter. Summer, 1969. Handwritten, painstakingly, by the man at left, whose right hand and both legs are still in Vietnam.

“All Wounded Marines,” wrote the corporal, “dig Ward M, for here we have an Angle of Mursey. She has a Smile for you and me, and no wonder we are all Doing so well. Here is Truly Heaven’s Greatest Angle of Mursey, so Please Angle, never leave us, for we couldn’t live without you. You see, we built our whole World around your smile, Miss Randles, and We all love You.”

Right about here a normal magazine article would go on to explain how Ensign Susan Randles was going to rotate to a hospital ship, but instead she fell in love (with the officer who ran the brig!) and got married, and earned her doctorate, and returned to The Bluff to be a beloved professor and dean, but let’s not go there today. Let’s stop right here with Susan Randles Moscato holding her friend Tony’s letter in her hand, and her hand is shaking a little, and no one says anything for a while, and then she says, quietly, fiercely, heroes, do you understand?

Yes. Yes, we do.