Congratulations to the Gonzaga Bulldogs, West Coast Conference Champions, for their appearance in the Championship Game of the 2017 NCAA Basketball Tournament. UP and Gonzaga were founding members of the WCC in 1952, two Catholic colleges competing before and since.

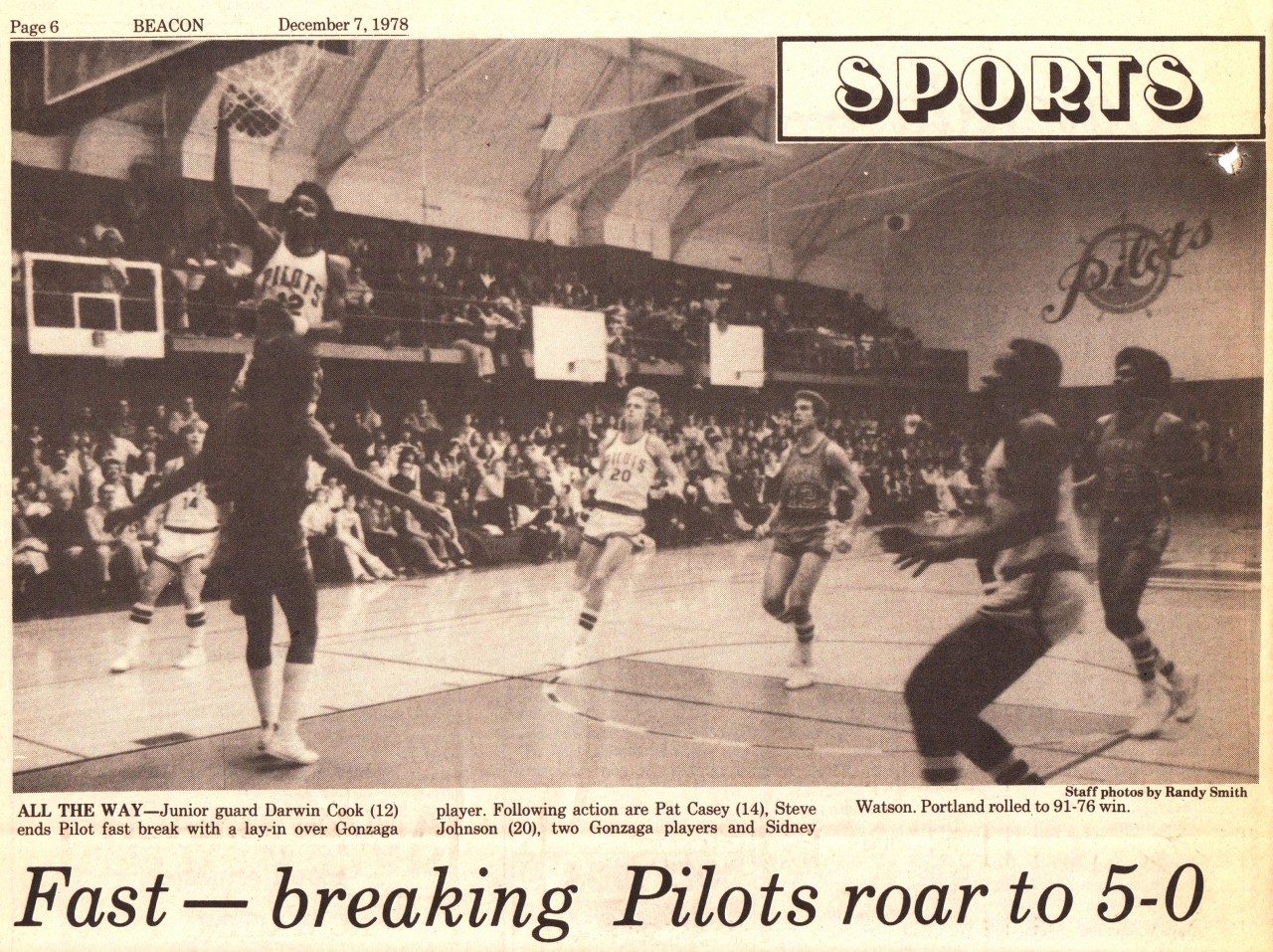

A not always polite rivalry. Although the last Men’s Conference game held in venerable Howard Hall occurred in spring 1981, earlier in December 1978, the Portland – Gonzaga game in Howard so rocked the court, stands, and the building itself that Fire Marshalls and student fans feared the worse (but no worries, the Pilots were off to a 5-0 start that season, defeating the Bulldogs 91-76). All later appearances in rivalry against Gonzaga have commanded a larger, sturdier venue. In recent years Gonzaga sells out the Chiles Center as visitors meeting us on our home court.