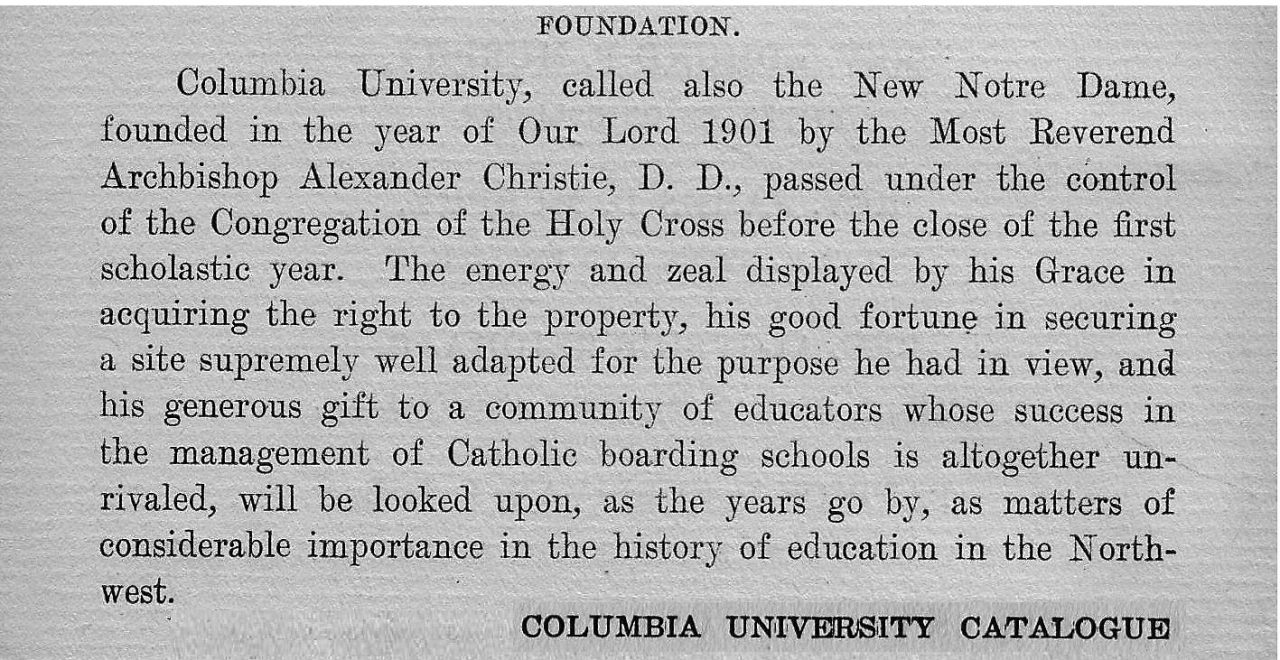

Archbishop Alexander Christie founded this school on the Bluff in 1901 intending to establish a Catholic University for Men. This ambition is too often simplified (and falsified) as ‘a college for male Catholics’, thereby reducing the mission to the demographic. The first issue of the University Catalogue (1902)—which provides statements concerning the history, mission, organization of the new institution—does not give evidence of any attempt to create some special Catholic club here at the north end of the growing city of Portland.

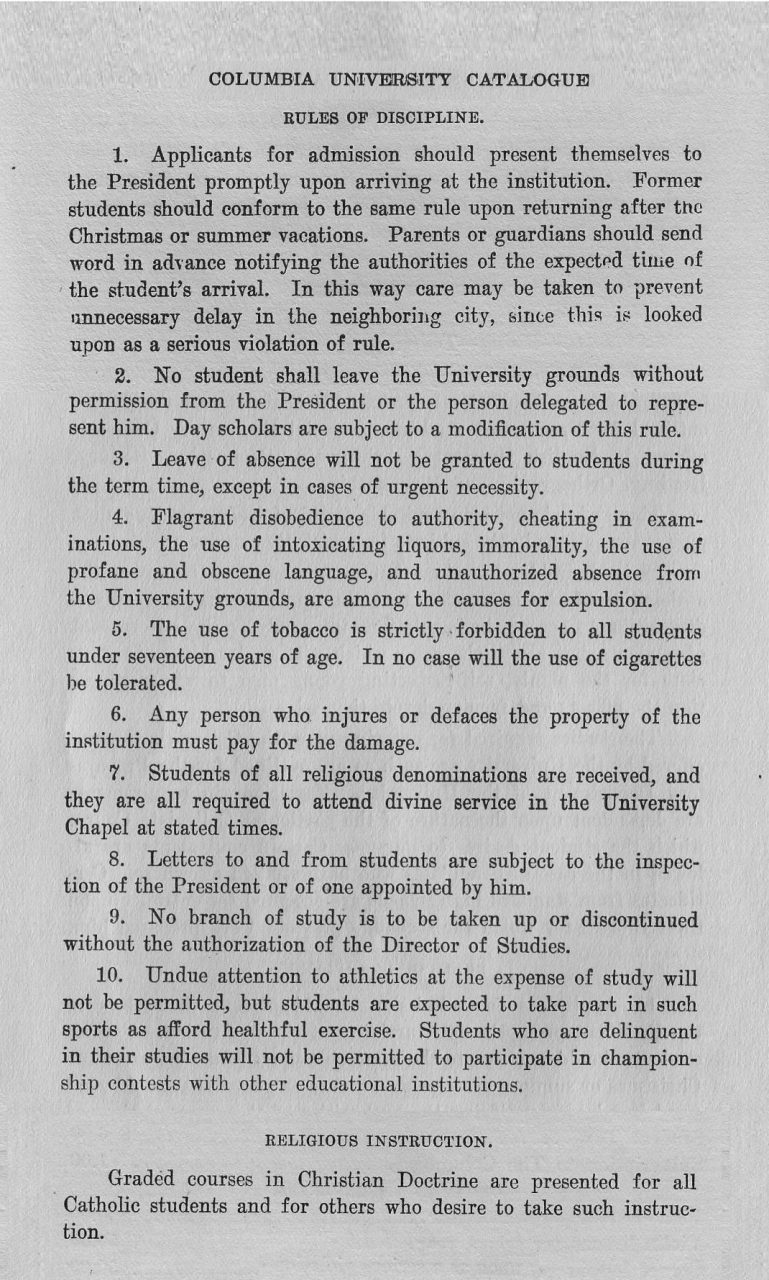

The ideals and tolerances of student conduct is described a few pages later;

Note particularly how in the regulation of student discipline, religious practice falls behind tobacco usage as a signal of the student’s moral standing. Also, while these paragraphs and rules are routinely reproduced in the pages of the Catalogue each year, the comment about a ‘New Notre Dame’ is stricken after the first year; and by 1907 the religious observance rule is expanded to read: “7. Although students of all religious denominations are received, the University is nevertheless a strictly Catholic institution, and all students are required to attend divine service in the University Chapel at stated times.” The mandatory stated-times, however, are not stated.

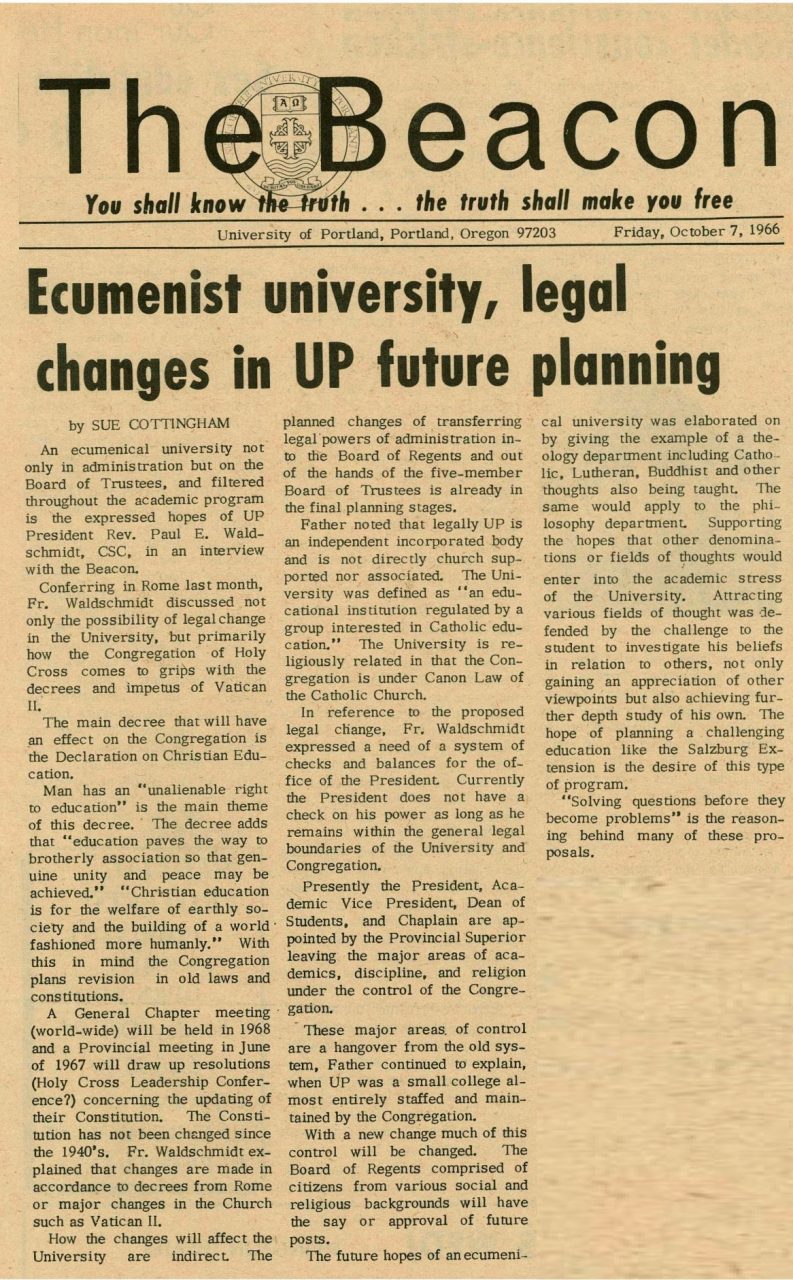

In fact the obvious tension between open-admission without religious test or discrimination, versus a policy of enforced observance means that the rationale and language of this requirement will continue to be adjusted and modified throughout the University’s history. Further, of course, the dialogue between ‘Catholic University’ and freedom of individual observance remains in tension still today.

Beginning about 1911 (and repeated with minor revisions until the 1950s), the Catalogue frames student conduct regulations in these words: “The Faculty maintain that an education which gives little attention to the development of the moral part of a youth’s character is pernicious, and that it is impossible to bring about this development where students are granted absolute relaxations from all Faculty government while outside the class-room. A young man must learn obedience to law by the actual practice of obedience, not merely by appeals to honor.

Yet this surveillance model is replaced in 1914. While repeating the formula: The Faculty maintain. &c., the University quietly admits the disciplinary model is frankly paternal. But then expands this description in a new direction, a direction that reflects the priests and brothers own commitment to embodying the same model of life in their own religious fraternity. Transmitting education and ideals by living together side-by-side: “The Faculty and students form one big family, not only meeting in the class room but partaking of the same wholesome fare in a common dining-room, living in the same buildings, enjoying recreation together on the campus and attending Divine services in a body in the chapel. The underlying principle of the school is the combination of secular training with positive religious instruction in a constant religious atmosphere. The institution is strictly Roman Catholic but admits students of other denominations and respects their conscientious beliefs.”

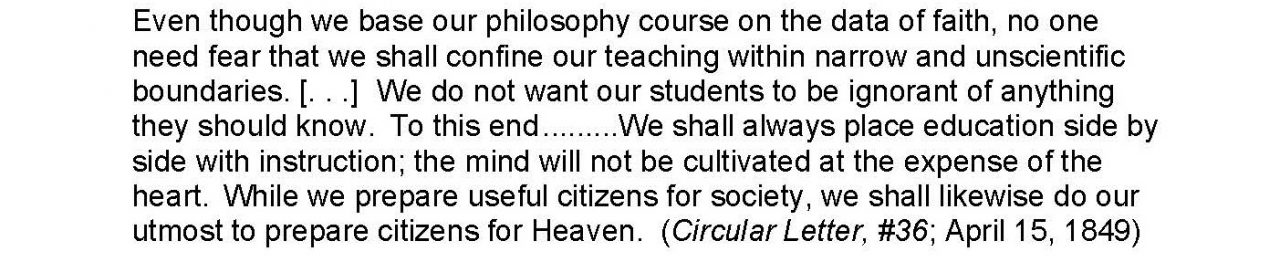

Here, showing awareness of an environment of pluralism, the values of honor and conscientious belief are restored and formally privileged, which is to say, expanding the dignity of the person over required uniform obedience to external regulations. And this, in turn, recovers a theme perfectly familiar to the Holy Cross Brothers and Priests insofar as it expresses agreement with the educational program found in the writings of the Reverend Basil Moreau, CSC, the Founder of the Congregation of Holy Cross.

Two further considerations apply for us when reading these student-life rules a century later. First, the imposition of religious observance was much diluted insofar as the larger percentage of students lived off-campus and beyond any system of supervision. Second, throughout the early twentieth century, The State of Oregon was actively hostile to religious-affiliated schools. Resulting in The Compulsory Education Act of 1922, which required that all primary education (ages 8-16) be conducted exclusively in public schools; effectively eliminating all private, military, or religious-based grammar and high school institutions. The result of a ballot initiative, the U.S. Supreme Court declared the measure unconstitutional before it could take effect in the state. (See, Lawrence Saalfeld, UP faculty 1959-61, Forces of Prejudice in Oregon 1920-1925; also, James T. Covert, A Point of Pride, pp. 63-64.) At the time of the legislation, our high school division (which could not have survived under the new law) was the financial driver and health of the school. Both the character and viability of the University thus centered upon resolution of the civic and internal dialogue around the role of religion in student and academic life. A dialogue that is complex, convoluted, and contemporary still today.

Leave a Reply