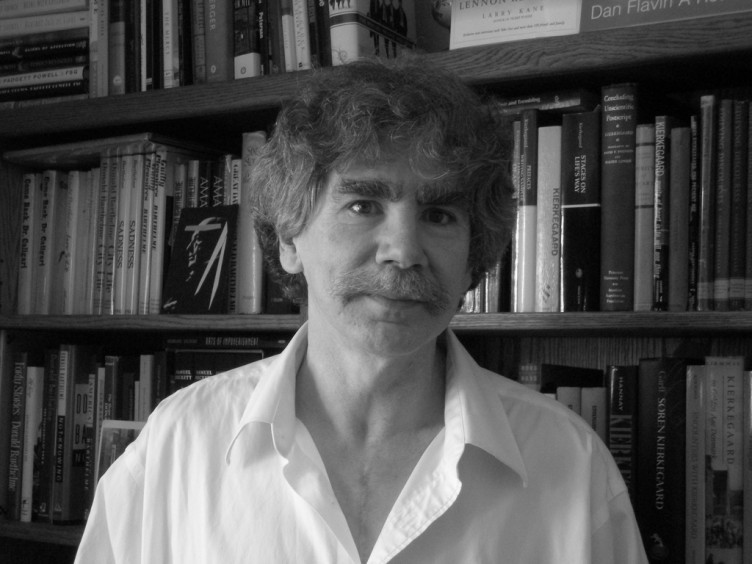

G. C. Waldrep is a poet and historian. He currently teaches at Bucknell University and serves as the editor for Bucknell’s literary magazine West Branch. Waldrep’s most recent poetry collection is Feast Gently. Waldrep was scheduled to be visiting UP tonight in the Brian Doyle Auditorium; however, due to concerns surrounding the COVID-19 virus, the…

Q&A with G. C. Waldrep