I couldn’t quite verbalize how I felt, so my words got twisted in my throat, making a home for themselves among other misunderstandings and lost conversations.

By Emily Neelon |

I am a walking existential crisis. I have been this way for as long as I can remember. In elementary school, I dreaded P.E. and the slightly anarchist team-picking process with an extra sense of panic, spending my morning and afternoon recesses writing sci-fi short stories. My three years of middle school involved a lot of bad haircuts I clearly didn’t think through and membership in the podcasting club and failed scores on my pre-algebra retake tests. I was painfully shy and uncomfortable in my own skin at my ultra-competitive, all-girls, private high school where I made it onto the varsity track team by default of being an upperclassman and was the kind of person everyone thought was in band, except I didn’t have any musical talent. I never quite matched up to what was expected of me, which made me feel vaguely miserable and insecure. But, in the back of my mind, I planned on moving away for college – so I perfected the art of getting by. As I teetered across the stage in my five-inch heels and white, polyester gown to accept my diploma at my high school graduation, I felt elated. I was getting out! I was going to fine! I would never have to study math again! No one would know about the bad haircuts up in Portland! But things aren’t always that simple.

I am a walking existential crisis. My freshman year at University of Portland was no different. Like a virus, my worries mutated within the changing environment and the panic became rooted in my chest, an aching that permeated through my entire body until I couldn’t breath. A bad grade became a marker for inadequacy. A resume became an identity. A mistake became a failure, a failure that edged in and out and through me. While I appeared well adjusted on the outside, I became anxious in a way that wove through every part of me. I became sad in a way I couldn’t shake, a way that made feel truly and sincerely alone. The anxiety became depression, which became anxiety.

It had always been difficult for me to talk about this part of myself. I didn’t feel comfortable labeling my anxiety and depression. I liked to pretend that they weren’t there, or that I overcame them, but they always reemerged and I had a hard time being a functioning person. I was afraid that if I admitted to the intensity of these feelings, they would grow outside the scope of my control. I couldn’t quite verbalize how I felt, so my words got twisted in my throat, making a home for themselves among other misunderstandings and lost conversations. I rationalized away these fears, searching for reasonable explanations for the heaviness that wrapped around me. And I worked, way too hard, to match up to what was expected of me. Some days I broke the surface. Some days I didn’t.

Over the past couple of years, these feelings swallowed me whole. I began to experience paralyzing anxiety attacks, followed by periods of deep isolation. Sometimes, I was lucky enough for these attacks to happen at home, where I could curl up into a ball underneath my mustard-colored comforter and let the anxiety slowly dissolve until I fell asleep. But most of the time, these moments happened in very public places and I didn’t know what to do. I had anxiety attacks in the library. I had anxiety attacks at silent discos. I had anxiety attacks in class and at work and on buses. And as these anxiety attacks became more frequent and severe in their intensity, doing things that were not sleeping or eating carbs in my bed became hard. I needed to learn how to take care of myself. And so I finally did. Slowly, and with lots of help.

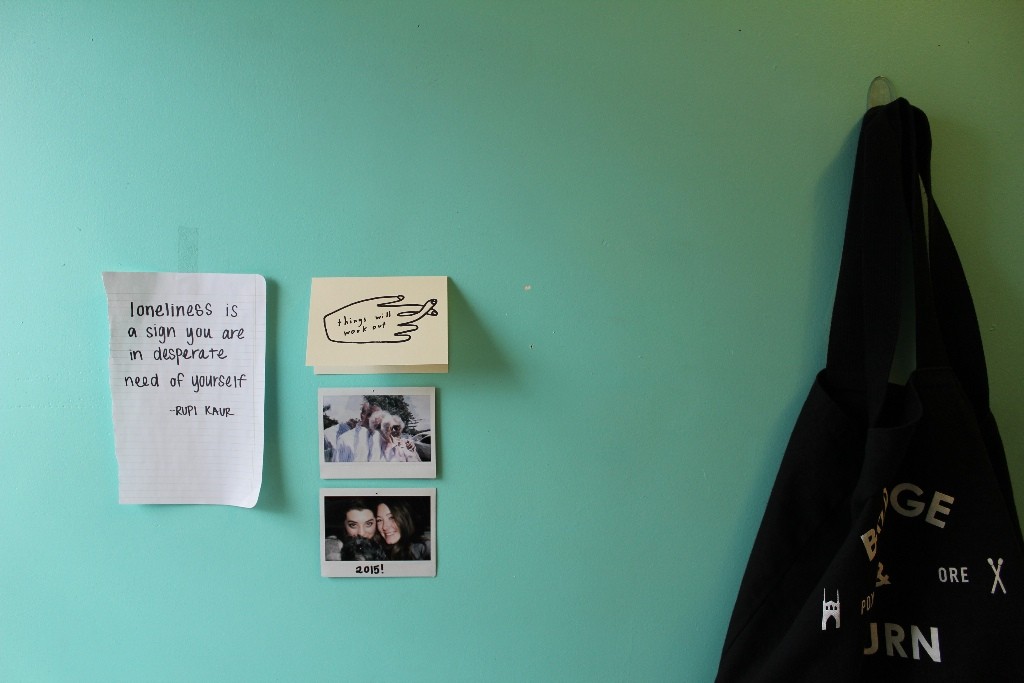

Taking care of myself looks like listening to a lot of Tame Impala, all day long, because there is no such thing as too much Tame Impala. Taking care of myself looks like going to therapist. It looks like asking for support from my friends and family. It looks like asking the dumb questions because I want to know the answers. It looks like eating a baguette in my bed and a long distance call to my best friend. It looks like redefining what success looks like. It looks like some bad days and a lot of good ones. It looks like forgiving myself for the brain that is mine, a brain that works differently.

When I look back on my experiences with debilitating mental health and slow healing, I remember so many moments of crushing self-doubt that were equally matched by moments of incremental growth and clarity. And although I sometimes still feel panicked, I’ve begun to realize I am not alone in feeling the sense of shame that accompanies ongoing and consistent anxiety and depression, labeled or unlabeled, defined or abstract. It’s been four years. As much as I’ve changed during this time, I am still a walking existential crisis. Some days I break the surface. Some days I don’t. I am not always ok. And that is ok.

Emily Neelon is a senior Communication major at the University of Portland and the Digital Content + Development Intern for the Career Center. She can be reached at neelon17@up.edu.

For more on mental health and self care, check out How to: Push past the fear of failure

Thank you for sharing, Emily. I’ve dealt with the exact same thing since fourth grade and it culminated in that lovely high school we went to until one night I woke up in my dorm room in college and couldn’t breath because of my panic attack. I didn’t think I would be able to stay at school since I was having 5-7 panic attacks a day but thankfully with the support of friends and doctors I was able to find a solution. If the world had more people like you that shared their story, it would be a happier place.